Using a neural net to match dialogue with characters in Star Trek: Deep Space Nine

Overview

AI and neural networks are all the rage these days, but how hard are they to make and use? Could someone with programming and data experience, and a Macbook Pro whip one together for a non-trivial problem, despite having no experience with neural networks?

I spent about a week and a half and created something to take lines of dialogue from a tv show (Star Trek: Deep Space Nine) and identify the speaker. And it works! Though it turns out this is a very difficult problem and even I, as a fan of the show, am only barely better than the AI, and neither of us can beat 25% accuracy.

I should also point out there will be some spoilers ahead, in the unlikely case you, dear reader, are invested in watching this almost 25-year-old show for the first time.

If you’re inclined, you can see my whole implementation in a Jupyter notebook.

Problem Definition

The goal of this project isn’t actually solve the problem I’ve set for myself; let me explain

The problem I’ve set is to take a line of dialogue and identify which character spoke the line. The initial dream was to train a GAN (generative adversarial network) to have little conversations, but we need to find a project that is small enough to tackle for a very first neural network, and that’s going to be simply identifying speakers. If we can get this to work, then we have permission to dream bigger in some future blog post!

The true goal of this project is to build a prototype neural network, do it quickly, and learn as much as I can. Having a good classifier neural net is a nice thing to make, but the real goal is to be able to do this again even better on the next project!

To get a feel for the problem, here are some examples of lines of dialogue taken at random from the show’s 173 episodes:

| Character | Line |

|---|---|

| DUKAT | Then call to them. |

| O’BRIEN | It’s not so bad. |

| EZRI | What are you getting at, Benjamin? |

| QUARK | You’ve got a deal. |

| QUARK | I can take it. Tell me. |

| GARAK | We’ve cleared their defense perimeter. |

| JAKE | What do you think I should say? |

| SISKO | Take us in a little closer. |

| ODO | Why shouldn’t I? |

| NOG | I liked The Searchers better. |

Clearly it’s going to be a challenge when the dialogue is very generic, but it’s not an impossible task. Hopefully we can identify Captian Sisko’s imperative declarations, Quark’s commercial obsessions, or Ezri and Dax being the few characters to ever say “Benjamin”.

The Data

To match dialogue with speakers, we first need access to the dialogue. Initially I had planned to use the closed-captioning, but you can actually find scripts to the entire show on a fan website called Star Trek Minutiae. Important to note is that the scripts are copywrited and I have not obtained any permissions from the creators or owners, but we should be okay using this in a ‘fair-use’ context, which I believe applies to this project.

The scripts are all in simple .txt files and we need to transform them into a database of dialogues and speakers. That means isolating the spoken lines from the stage directions, scene descriptions, copywrite notices, and other information included in the script. Thankfully the spoken dialogue is almost always formatted in the same way: speaker’s name in all caps on its own line, followed by the dialogue all indented by three tabs, followed by a blank line. This pattern works quite well, and with a few other corrections (like merging DAX, DAX (O.S.), DAX'S VOICE, etc. all into DAX) we can get a good set of lines matched with their speakers.

Neural networks tend to like numerical values as their inputs, not strings. Tokenization is used to resolve this; a string is converted into a list/array of tokens (represented by some index in a dictionary) and each token conveys some hopefully atomic meaning (ie: we don’t benefit from splitting tokens any further). A sophisticated tokenization algorithm would break a phrase like A cat's ears into ['a', 'cat', '\'s', 'ear', 's'] or rather the indexes of the tokens, something like: [4, 17, 8, 139, 6], paying attention to plurals and suffixes etc. However, for a simple model, I just created a vocabulary out of each unique individual word (characters separated by spaces) in the corpus, and assigned each as their own token, so words like ear and ears are treated as two entirely unique words. To help speed things up, I designated a rare_word token and reassigned all words with less than 20 occurences to that token, so the network can easier deal with all the invented lingo of the Star Trek universe and our vocabulary doesn’t balloon too large, reducing our vocabulary from 9270 to 814.

One difficulty with the data is that some lines are very short, while some are almost soliloquys. To avoid implementing something complex to deal with long lines, like LTSM, I’ve restricted the lines of dialogue to only be between 3-8 words. I tried relaxing this restriction, but the model’s performance decreased significantly. I believe this is related to the nature of RNN’s: since they use the output of the last hidden state in the chain, the last few input vector elements carry the majority of the impact. Highly variable line lengths are a problem for this kind of model.

Lastly, I restricted speakers in the problem to only those who spoke at least 1000 sentences. Sorry generic TACTICAL OFFICER, but we aren’t very interested in what you have to say. This leaves us with 14 characters who I think represent the main cast of the show. A challenge we’ll tackle soon is that they have a very non-uniform representation in our dataset:

| Character name | Lines |

|---|---|

| SISKO | 13329 |

| KIRA | 8158 |

| QUARK | 7863 |

| BASHIR | 7852 |

| O’BRIEN | 7310 |

| ODO | 6993 |

| DAX | 5709 |

| WORF | 3123 |

| GARAK | 2594 |

| DUKAT | 2313 |

| JAKE | 2111 |

| ROM | 1937 |

| NOG | 1849 |

| EZRI | 1519 |

Note that Jadzia Dax is DAX and (spoilers!) Ezri Dax is Ezri.

The Model

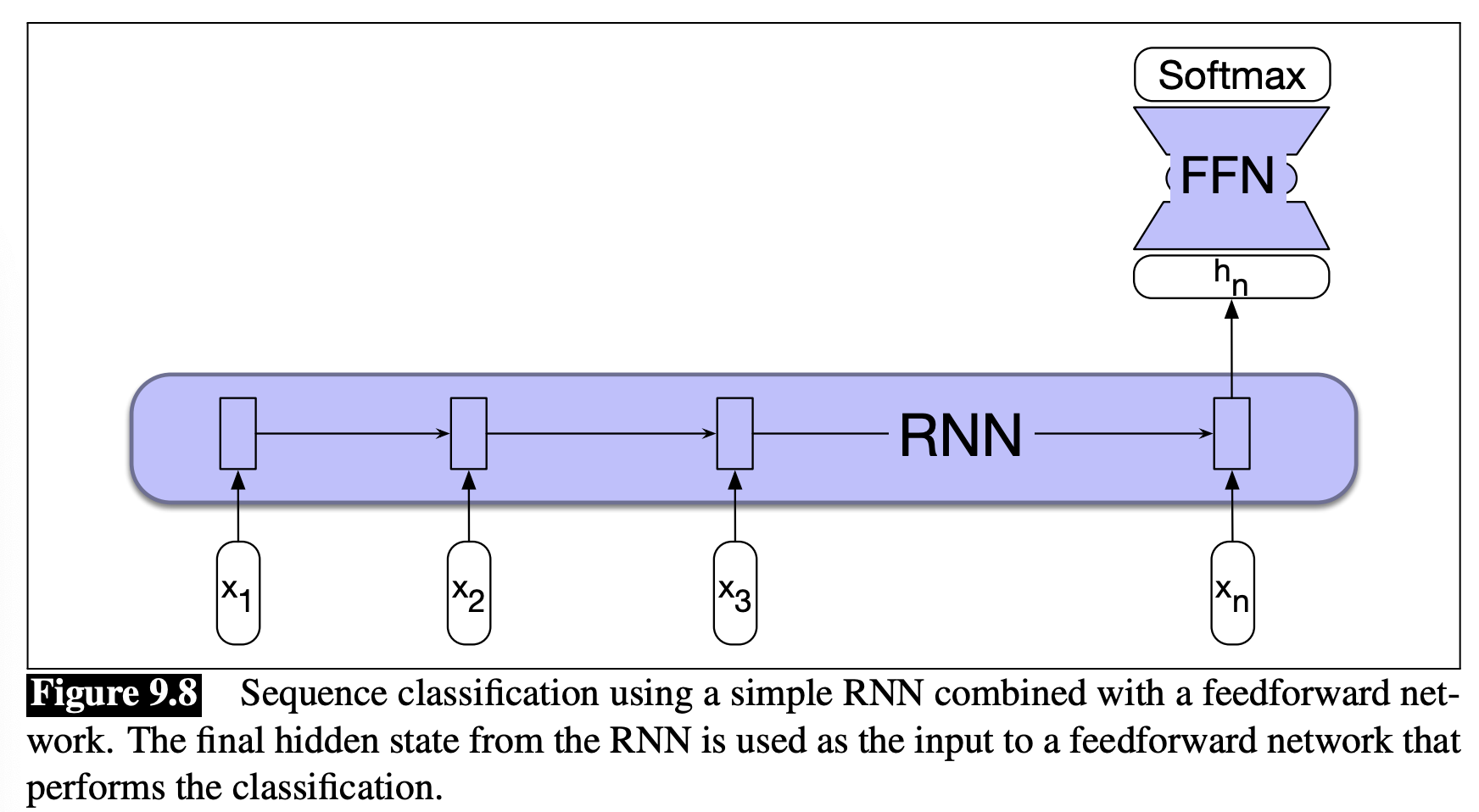

The model is a recursive neural network (RNN), with embedding, whose output is interpreted by a feed forward network. Since we’re identifying the speaker, this is a classification problem. This diagram from Speech and Language Processing by Jurafsky and Martin illustrates this set-up nicely, albeit without the embeddings.

A neural network can almost accurately be imagined to be a series of matrices and simple non-linear functions (like tanh, sigmoid, or ReLU). You give it an input vector, multiply this by a matrix, apply the non-linear function, and repeat, until you have an output value or vector representing what you wanted it to predict. Each of these repetitions transforms our input to some hidden intermediate values, then sometimes from hidden values to more hidden values repeatedly, and eventually from the hidden values to the output. Each of these stages of hidden values are called layers. As it trains, the values of these matrices are altered to try to get better predictions. There are a few more steps than that, but this is the basic idea. In our problem, the input vector is a list of indices for words in the line of dialogue, and the output is a vector with one element for each character that expresses the confidence that this character is the one who spoke. Our predicted speaker is the maximum of that output vector.

Anyone who’s taken a linear algebra class before will know that matrix multiplication is extremely picky about the number of dimensions in the vectors and matrices. Our input vector, being a line of dialogue, can have a wide variety of lengths. There are a variety of ways to tackle this problem, like a bag-of-words approach, an n-gram model, or a transformer approach, but for this project I used a recursive neural network. How this works is that the network is only fed one word at a time. I used just one hidden layer, which is then fed, along with the next word, back into the network. This happens repeatedly until there are no more words, in which case the final hidden layer gets transformed by one more matrix & activation function combo (and a softmax, but don’t worry about that), into our output. By doing this, we can process arbitrarily long input strings, although typically these sorts of networks have trouble remembering important information when given inputs that are too long. There are methods to deal with this, such as Long Short Term Memory (LSTM), but I wanted to keep this network as simple as I could while I’m still learning.

The last step to the model is actually adding a first step to help us deal with that large vocabulary. Instead of trying to learn patterns from ~800 words, we’d rather turn those words into something that understands a bit of the meaning and function of those words, and learn patterns from those meanings. This is called embedding, and it essentially just adds one extra layer to our neural network. This embedding layer is trained at the same time as the rest of the network, but it helps simplify the problem for the later layers.

The Training

In a model like this, we refer to the weights in the neural network as our parameters. We train them by feeding our model input vectors and seeing its prediction, then altering the parameters based on the differences between the output and the correct value. To make sure we are training a general model and not memorizing the training data through overfitting, we split the data into two groups, a training set and a test set, so we can evaluate the model on data we’ve never seen before.

There are some parameters to the model that have more to do with the structure of the model rather than the weights, values such as the learning rate, number of neurons, and vocabulary size. We call these new dials metaparameters or hyperparameters. How can we train these? We could fit these similarly to how we do our ordinary parameters, but a simpler option is to do a grid search where you test a variety of values close to your initial guess and pick the combination that works the best. But again, we want this to be an even simpler project, so I simply tried doubling or halving each hyperparameter once, and testing them one at a time. This is another process which is susceptible to overfitting, so we again split our training data, breaking off a chunk called the validation data, and use this validation data to ensure we have a good result for our hyperparameter tuning.

For this project I used 20% of the total data as the test dataset, and 20% of the remainder as the validation dataset, with the rest being training data. The training data is used to train the network from scratch for each hyperparameter combination, which is validated against the validation set. Once I was happy with a combination of hyperparameters, the model is trained again from scratch but for a much longer time using the training + validation datasets, and this is tested against the validation set.

One of the complications of the dataset is that characters speak with extraordinarily varied frequencies; ie: some characters talk a lot more than others. We don’t want this to bias our model to simply guessing the most commonly speaking characters all the time, so instead of iterating through the entire training set, I uniformly selected a character at random, then selected one of their lines at random. I would repeat this until I was confident the training was long enough to learn the major features of the data, but keeping in mind that we are essentially over-sampling the less verbose characters’ lines. This should not be too much of an issue unless our training size for a character gets significantly bigger than the actual number of lines spoken by that character.

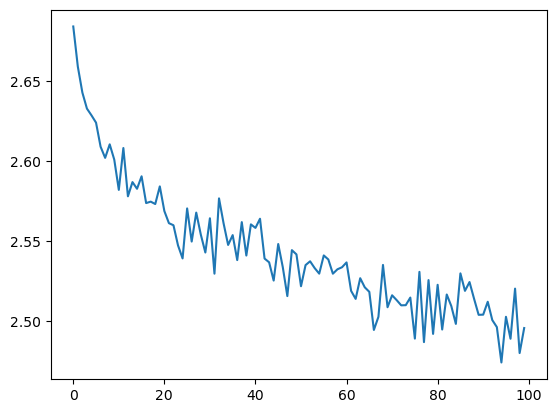

The model learns based upon minimizing its wrongness, or loss. There are different ways of quantifing loss, but for this model I settled on using cross-entropy. This loss metric is actually one of the hyperparameters I tried out; learning using cross-entropy loss performed better than using the negative log likelihood. We can look at the loss over time, and hopefully see that as the model learns, the loss steadily decreases. Over the 200 000 final training dialogue inputs, here is the loss:

We can see that the loss is decreasing with increasing training, which implies that the model is actually learning! Eventually this training should yeild diminishing returns, and although it looks like we could continue training for a longer time, I’m not actually too interested in the final result, just proving the concept and learning how to make neural networks.

The Results

We can check the accuracy of the model by looking at how often it made the correct guess against the testing data. It was correct 16% of the time! While this might not sound like very much, it is significantly better than the 1/14 ~= 7% accuracy we would expect if it was performing random guesses and had learned nothing. (Technically we can get professional and say we can reject the null hypothesis of random guesses, which is a simple binomial distribution, by hundreds of sigma, to the point that calculating the p-value is quite meaningless). There are other metrics besides accuracy, but I feel like accuracy is best for this problem.

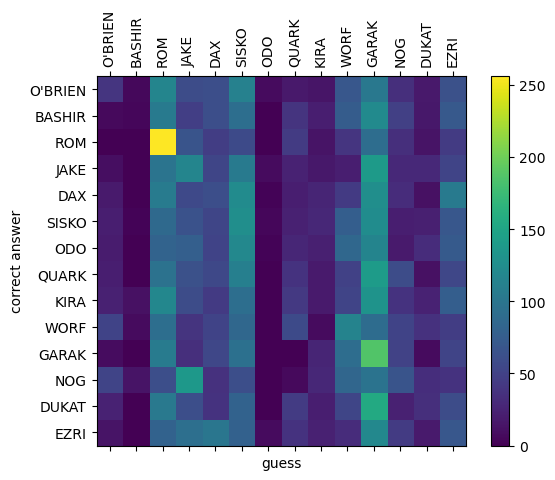

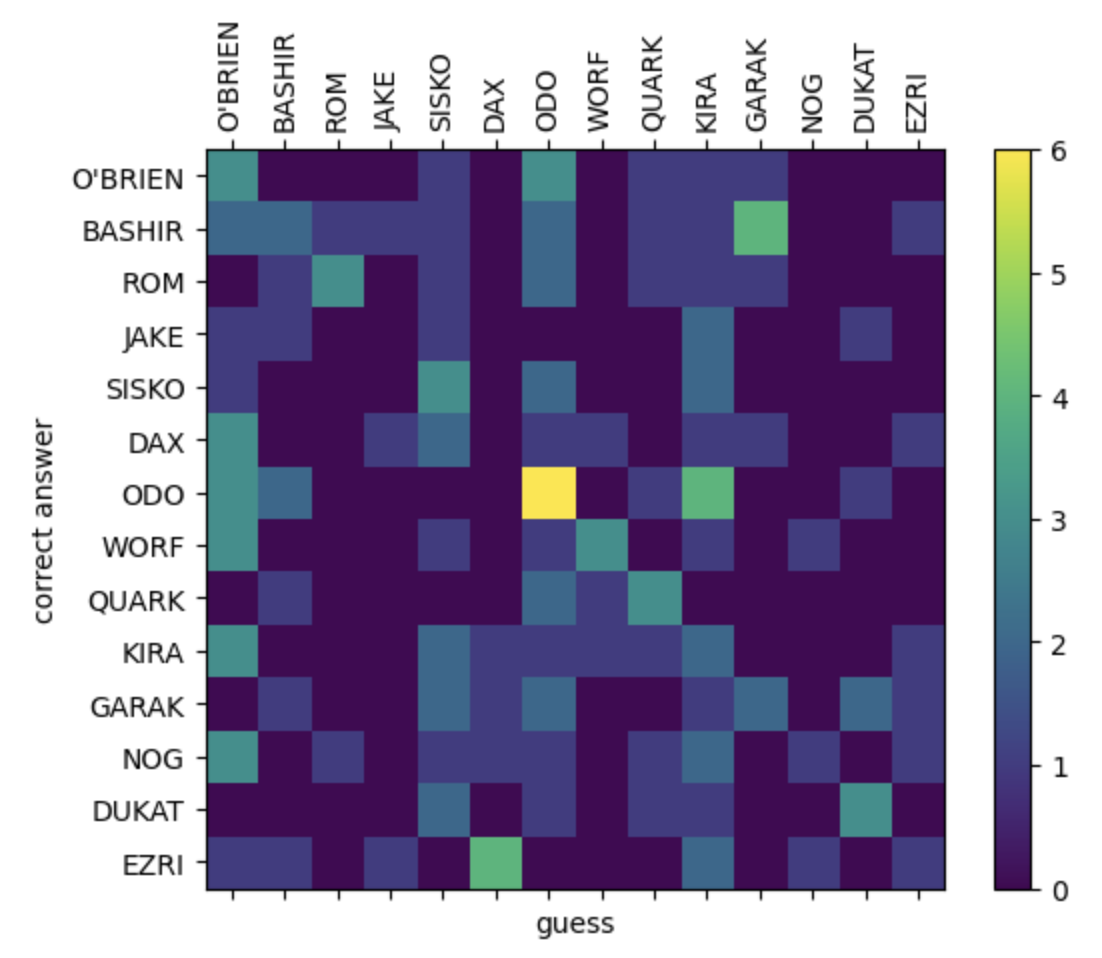

We can also look at which characters it can identify correctly and which characters it gets confused using what’s called a confusion matrix. Here we compare guesses with the correct answers in a square matrix. We hope we get a nice diagonal line from top-left to bottom-right, as this would mean we’ve guessed every character correctly. Here’s what it looks like for our trained model:

It’s not the prettiest… the vertical bands indicate the network has a tendency to guess the same characters over and over, disregarding the input. But we can see some characters like Garak and Rom are actually identified fairly well. Since they have a quite unique voice (in terms of vocabulary and sentence structure), it makes sense they are where the model performs the best. We can also see some peculiarities, for example the model will identify Nog as Jake but will rarely identify Jake as Nog.

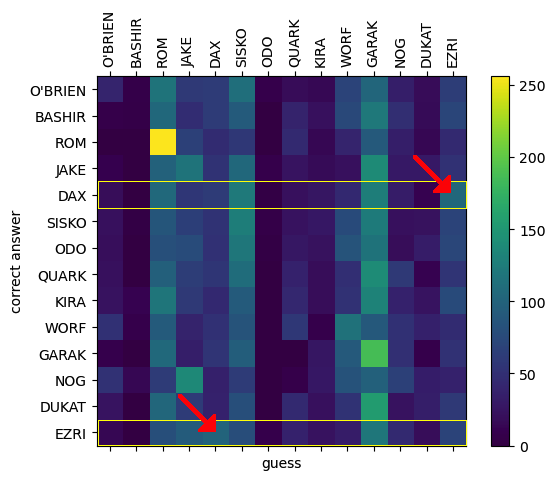

And (spoilers) a show’s fan will be delighted to see the confusion between Jadzia Dax and Ezri Dax, beautifully mirroring these characters’ confusion between themselves! The yellow boxes in the plot above are situations when the speaker is either Ezri or Dax, and the arrows highlight where they are mis-identified as each other.

I additionally wanted to check how well this model could perform relative to a human who is a fan of the show (myself). After testing myself with 150 dialogues, I got 32 correct answers giving me an accuracy of about 21%. It is actually really hard! How do you identify someone who says What does he want with us?, would you correctly identify that line as spoken by Dax? The model might not be able to outperform a human, but the fact that it even comes close is astonishing! Here’s my personal confusion matrix for reference:

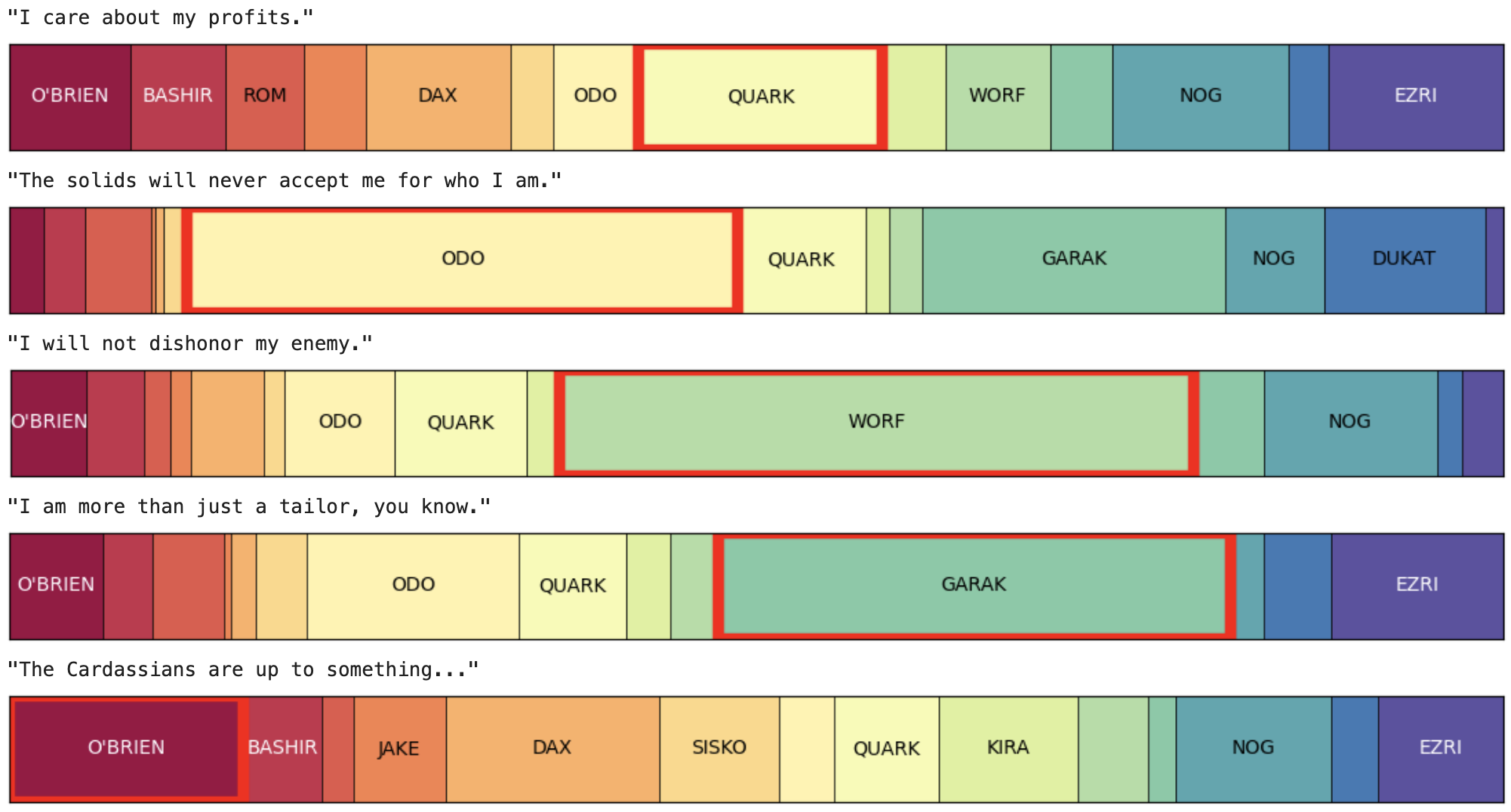

We can extend the use of this model to make predictions about which character is most likely to have said some line that never actually appears in the show. Up until this point I’ve shown you the character that the model believes most likely spoke, but it actually returns a probability of the line being spoken for each character, based on the model’s confidence. For example, here are a series of lines I’ve invented to be very typical for a character and that sound like they are from the show. We can see when the model is confident in the hypothetical speaker, and when it has more doubts.

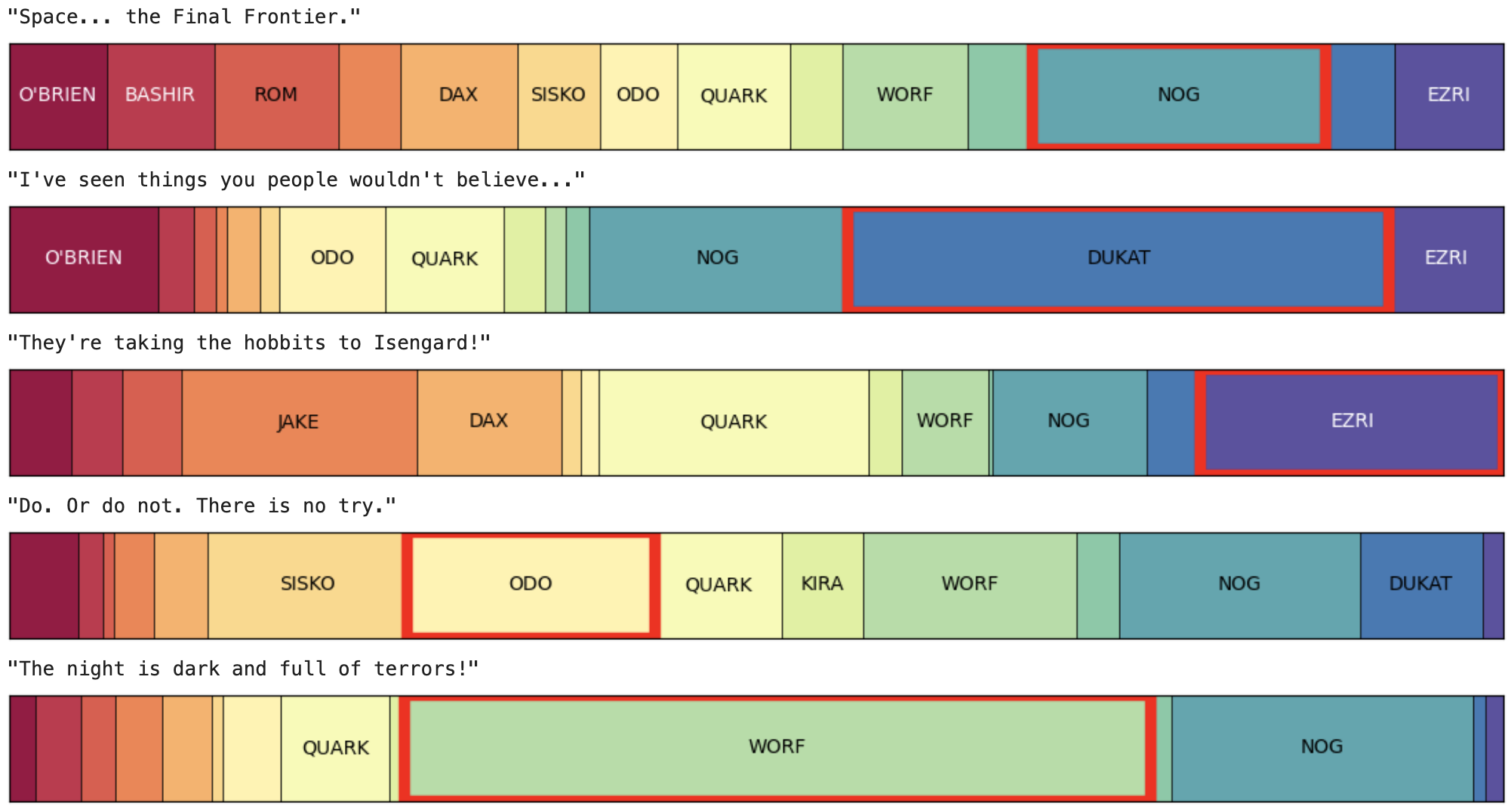

Although less useful, it can be a lot of fun to do this with lines from other franchises and see which DS9 character best fits the role:

All together I’d call this project a success. With a MacbookPro, internet searches, one and a half weeks, and some data, you really can build an AI / neural network from scratch with no experience on the subject! RNN’s are just one of a great many frameworks for a neural network, but it was a great challenge to get started in this burgeoning field. Not only did I learn a lot about neural networks, but a lot about one of my favourite shows at the same time!

Further Reading

I used pytorch to run the neural network, so of course their documentation proved indispensable. I particularly found a lot of use out of this similar tutorial about identifing origins of last names

This machine learning glossary proved handy to get a handle on several unfamiliar jargon words that I came across while learning. Though I’d probably call it a neural network glossary primarily.

Speech and Language processing by Jurafsky and Martin is a truly wonderful resource for learning the wide world of NLP. However much attention this book is receiving, it probably isn’t enough.

Lastly, of course, stack exchange and google are really the backbone of learning how to do anything these days, and using those is a fundamental skill that needs to be mastered before tackling a project like this.